Why Yes, I Am Boring Enough To Read The Footnotes

Worse than that, I've been known to go read the references themselves

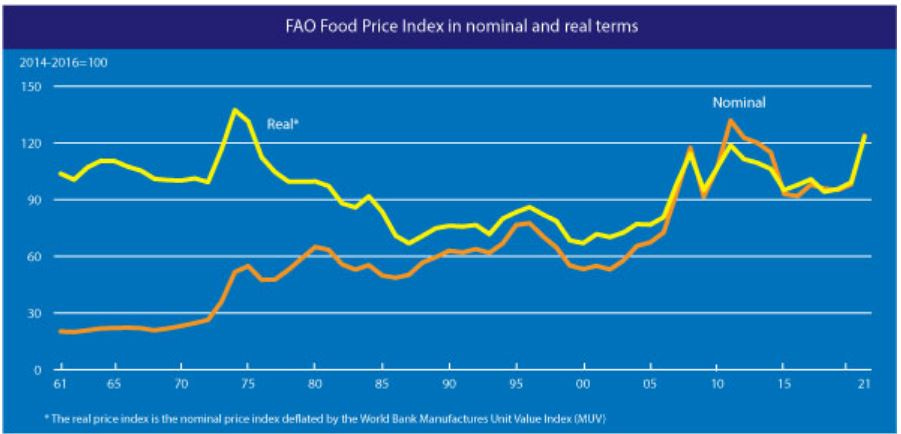

There’s a claim out today that global food prices are the highest they’ve been since 1975. This doesn’t quite accord with the lived experience so what’s going on here?

Global food prices have rocketed to their highest levels since 1975 in real terms. They will increase next year and remain elevated into 2023, according to economists at BCA Research.

Prices are already above levels seen during the last food crisis early last decade, which sparked social unrest across the world.

Pressure on fertiliser prices is set to intensify this winter after the gas crisis fuelled a near tripling in the key food cost input to record highs.

Yes, OK, we know that fertiliser prices are up because natural gas prices are. The Haber Process relies upon natural gas to make the ammonia that then makes the ammonium nitrate (I think that’s the chemistry?) which is the fertiliser that makes organic farming look, erm, a bit shit.

But high fertiliser prices now because high gas prices now wouldn't really be afflicting food prices now - largely what we’re eating now was planted and fertilised last year when gas prices were very much lower.

But OK, perhaps they’re looking at the commodity markets and futures prices and all that. Still seems a bit odd. So, why are we being told this highest since 1975 which seems so at odds with looking out the window?

One possible answer is simply that I’m using my own lived experience. Not that I’m rich, rich, you understand, but as someone in the top 10% in a rich nation I’m in the top 1% of global incomes. Food costs are, according to the ONS for the UK at least, around 10% of household income, less for those further up the income scale. This is, of course, just another way of pointing out how fabulously wealthy we all are in any historical or global sense.

A 20%, 50%, rise in food prices will lead to a little bit of substitution and a hey ho, so what for most of us in this situation.

I might also be making that error of comparing myself in 1975 with myself today. That change from spending the newspaper round earnings to the fortunes to be had being rejected by newspaper editors could have skewed my view.

Or, well, maybe there’s something else here.

So the UN is parping about how global food prices are up. And they are using this measurement, the Food and Agriculture Office (of the UN) food price index. Seems fair enough, UN uses a UN measure.

OK, that’s not entirely up to date but fair enough, by this measure it looks like real food prices are at least close to being a high as they were in 1975.

But there’s something kooky about the difference there between real and nominal prices. Nominal is before accounting for inflation of course, real is after.

Well, OK, real, real prices are how much effort do you have to put in to get summat? With food prices, say, how many hours work does it take to gain 1,000 calories of wheat? And that is the way - generally the, not just a - way that real incomes are estimated over centuries and millennia. But we’re not doing that, still it looks odd.

Real incomes have been rising this past 60 years. We’ve seen the biggest reduction in absolute poverty in the history of our species. So our real prices here - or, the same thing but working the other way, our deflator from nominal to real - aren’t connected to incomes. Because as a portion of real incomes food has been plummeting in price these decades.

It’s also not general inflation over that period. Well, not US $ inflation, $1 in 1961 is about $8.65 now in purchasing power. Eyeballing that index there they’re using about half that inflation rate. Or, the way deflators work, they’re listing - in US $ at American prices - food as being about twice as expensive compared to 1961 as it actually is. This accords with our observations about food as a percentage of household budgets where it’s more than halved - at the same time as folks have gone from almost not eating out at all to doing so maybe half the time.

Sure, global prices and US prices aren’t the same thing but there is still something not to, - ahaha - taste about this food price thing they’re trying to tell us.

So, what have they actually used as their inflation measure, deflator?

“The real price index is the nominal price index deflated by the World Bank Manufactures Unit Value Index (MUV)”

Which sounds a bit weird. Can’t really find the proper page for this (it returns as “Nope, not here!”) but we have an explanation:

A proxy for the price of developing country imports of manufactures in U.S. dollar terms, used to assess cost escalation for imported goods. Update twice a year, the index is a weighted average of export prices of manufactured goods for the G-5 economies, with local-currency based prices converted into current U.S. dollars using market exchange rates. Contains historical data from 1960 through 2007 and projections through 2020.

Umm, no. Really, just no.

There’s an old idea called “the scissors”. The terms of trade for agricultural folks get worse and worse as food prices go down faster than those of manufactures. So, that peasant scratching himself behind the pig barn has to grow ever more food over time in order to be able to afford the same amount of the production of the rest of society.

This measure of relative manufacturing and agricultural prices is useful in detailing exactly that process. Note what the scissors also says - food prices decline relative to manufactured goods prices. Or, equally true, productivity in agriculture increases faster than that in manufactures. They’re the same statement. This is also why the number of peasants has declined so much, we get ever more food from the labour of a person so we need fewer people over time growing food. Again, the same statement.

What this measurement isn’t useful as is a general inflation counter, deflator, for food prices. It’s way, way, too specific for that. It’s the price of food compared to manufactures exports from G5 nations. Say, the relative price of wheat and a Trent 1000 engine from Rolls Royce.

Well, OK, perhaps it might even be an interesting number. But it’s not a useful one for what is being attempted here, as a general measure of the cost of food around the world.

Compared to incomes food prices are way, way, down. Compared to general inflation, food prices are way down. Compared to the value of G5 manufactured exports food prices are about where they were in 1975.

Hmm, yes, let’s all run around screaming like soon to be headless chickens about the civilisational problems about to stem from that third measurement, shall we?

Our lesson for the day being that checking footnotes is just so, so, boring.